numerical-model

Type of resources

Topics

Keywords

Contact for the resource

Provided by

Years

Formats

Update frequencies

-

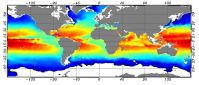

he Global ARMOR3D L4 Reprocessed dataset is obtained by combining satellite (Sea Level Anomalies, Geostrophic Surface Currents, Sea Surface Temperature) and in-situ (Temperature and Salinity profiles) observations through statistical methods. References : - ARMOR3D: Guinehut S., A.-L. Dhomps, G. Larnicol and P.-Y. Le Traon, 2012: High resolution 3D temperature and salinity fields derived from in situ and satellite observations. Ocean Sci., 8(5):845–857. - ARMOR3D: Guinehut S., P.-Y. Le Traon, G. Larnicol and S. Philipps, 2004: Combining Argo and remote-sensing data to estimate the ocean three-dimensional temperature fields - A first approach based on simulated observations. J. Mar. Sys., 46 (1-4), 85-98. - ARMOR3D: Mulet, S., M.-H. Rio, A. Mignot, S. Guinehut and R. Morrow, 2012: A new estimate of the global 3D geostrophic ocean circulation based on satellite data and in-situ measurements. Deep Sea Research Part II : Topical Studies in Oceanography, 77–80(0):70–81.

-

'''DEFINITION''' The CMEMS NORTHWESTSHELF_OMI_tempsal_extreme_var_temp_mean_and_anomaly OMI indicator is based on the computation of the annual 99th percentile of Sea Surface Temperature (SST) from model data. Two different CMEMS products are used to compute the indicator: The North-West Shelf Multi Year Product (NWSHELF_MULTIYEAR_PHY_004_009) and the Analysis product (NORTHWESTSHELF_ANALYSIS_FORECAST_PHY_004_013). Two parameters are included on this OMI: * Map of the 99th mean percentile: It is obtained from the Multi Year Product, the annual 99th percentile is computed for each year of the product. The percentiles are temporally averaged over the whole period (1993-2019). * Anomaly of the 99th percentile in 2020: The 99th percentile of the year 2020 is computed from the Analysis product. The anomaly is obtained by subtracting the mean percentile from the 2020 percentile. This indicator is aimed at monitoring the extremes of sea surface temperature every year and at checking their variations in space. The use of percentiles instead of annual maxima, makes this extremes study less affected by individual data. This study of extreme variability was first applied to the sea level variable (Pérez Gómez et al 2016) and then extended to other essential variables, such as sea surface temperature and significant wave height (Pérez Gómez et al 2018 and Alvarez Fanjul et al., 2019). More details and a full scientific evaluation can be found in the CMEMS Ocean State report (Alvarez Fanjul et al., 2019). '''CONTEXT''' This domain comprises the North West European continental shelf where depths do not exceed 200m and deeper Atlantic waters to the North and West. For these deeper waters, the North-South temperature gradient dominates (Liu and Tanhua, 2021). Temperature over the continental shelf is affected also by the various local currents in this region and by the shallow depth of the water (Elliott et al., 1990). Atmospheric heat waves can warm the whole water column, especially in the southern North Sea, much of which is no more than 30m deep (Holt et al., 2012). Warm summertime water observed in the Norwegian trench is outflow heading North from the Baltic Sea and from the North Sea itself. '''CMEMS KEY FINDINGS''' The 99th percentile SST product can be considered to represent approximately the warmest 4 days for the sea surface in Summer. Maximum anomalies for 2020 are up to 4oC warmer than the 1993-2019 average in the western approaches, Celtic and Irish Seas, English Channel and the southern North Sea. For the atmosphere, Summer 2020 was exceptionally warm and sunny in southern UK (Kendon et al., 2021), with heatwaves in June and August. Further north in the UK, the atmosphere was closer to long-term average temperatures. Overall, the 99th percentile SST anomalies show a similar pattern, with the exceptional warm anomalies in the south of the domain. Note: The key findings will be updated annually in November, in line with OMI evolutions. '''DOI (product)''' https://doi.org/10.48670/moi-00273

-

'''DEFINITION''' Estimates of Ocean Heat Content (OHC) are obtained from integrated differences of the measured temperature and a climatology along a vertical profile in the ocean (von Schuckmann et al., 2018). The products used include three global reanalyses: GLORYS, C-GLORS, ORAS5 (GLOBAL_MULTIYEAR_PHY_ENS_001_031) and two in situ based reprocessed products: CORA5.2 (INSITU_GLO_PHY_TS_OA_MY_013_052) , ARMOR-3D (MULTIOBS_GLO_PHY_TSUV_3D_MYNRT_015_012). Additionally, the time series based on the method of von Schuckmann and Le Traon (2011) has been added. The regional OHC values are then averaged from 60°S-60°N aiming i) to obtain the mean OHC as expressed in Joules per meter square (J/m2) to monitor the large-scale variability and change. ii) to monitor the amount of energy in the form of heat stored in the ocean (i.e. the change of OHC in time), expressed in Watt per square meter (W/m2). Ocean heat content is one of the six Global Climate Indicators recommended by the World Meterological Organisation for Sustainable Development Goal 13 implementation (WMO, 2017). '''CONTEXT''' Knowing how much and where heat energy is stored and released in the ocean is essential for understanding the contemporary Earth system state, variability and change, as the ocean shapes our perspectives for the future (von Schuckmann et al., 2020). Variations in OHC can induce changes in ocean stratification, currents, sea ice and ice shelfs (IPCC, 2019; 2021); they set time scales and dominate Earth system adjustments to climate variability and change (Hansen et al., 2011); they are a key player in ocean-atmosphere interactions and sea level change (WCRP, 2018) and they can impact marine ecosystems and human livelihoods (IPCC, 2019). '''CMEMS KEY FINDINGS''' Since the year 2005, the upper (0-2000m) near-global (60°S-60°N) ocean warms at a rate of 0.9 ± 0.1 W/m2. Note: The key findings will be updated annually in November, in line with OMI evolutions. '''DOI (product):''' https://doi.org/10.48670/moi-00235

-

'''DEFINITION''' Estimates of Ocean Heat Content (OHC) are obtained from integrated differences of the measured temperature and a climatology along a vertical profile in the ocean (von Schuckmann et al., 2018). The products used include three global reanalyses: GLORYS, C-GLORS, ORAS5 (GLOBAL_MULTIYEAR_PHY_ENS_001_031) and two in situ based reprocessed products: CORA5.2 (INSITU_GLO_PHY_TS_OA_MY_013_052) , ARMOR-3D (MULTIOBS_GLO_PHY_TSUV_3D_MYNRT_015_012). The regional OHC values are then averaged from 60°S-60°N aiming i) to obtain the mean OHC as expressed in Joules per meter square (J/m2) to monitor the large-scale variability and change. ii) to monitor the amount of energy in the form of heat stored in the ocean (i.e. the change of OHC in time), expressed in Watt per square meter (W/m2). Ocean heat content is one of the six Global Climate Indicators recommended by the World Meterological Organisation for Sustainable Development Goal 13 implementation (WMO, 2017). '''CONTEXT''' Knowing how much and where heat energy is stored and released in the ocean is essential for understanding the contemporary Earth system state, variability and change, as the ocean shapes our perspectives for the future (von Schuckmann et al., 2020). Variations in OHC can induce changes in ocean stratification, currents, sea ice and ice shelfs (IPCC, 2019; 2021); they set time scales and dominate Earth system adjustments to climate variability and change (Hansen et al., 2011); they are a key player in ocean-atmosphere interactions and sea level change (WCRP, 2018) and they can impact marine ecosystems and human livelihoods (IPCC, 2019). '''CMEMS KEY FINDINGS''' Regional trends for the period 2005-2023 from the Copernicus Marine Service multi-ensemble approach show warming at rates ranging from the global mean average up to more than 8 W/m2 in some specific regions (e.g. northern hemisphere western boundary current regimes). There are specific regions where a negative trend is observed above noise at rates up to about -5 W/m2 such as in the subpolar North Atlantic. These areas are characterized by strong year-to-year variability (Dubois et al., 2018; Capotondi et al., 2020). Note: The key findings will be updated annually in November, in line with OMI evolutions. '''DOI (product):''' https://doi.org/10.48670/moi-00236

-

'''DEFINITION''' The Mediterranean water mass formation rates are evaluated in 4 areas as defined in the Ocean State Report issue 2 (OSR2, von Schuckmann et al., 2018) section 3.4 (Simoncelli and Pinardi, 2018): (1) the Gulf of Lions for the Western Mediterranean Deep Waters (WMDW); (2) the Southern Adriatic Sea Pit for the Eastern Mediterranean Deep Waters (EMDW); (3) the Cretan Sea for Cretan Intermediate Waters (CIW) and Cretan Deep Waters (CDW); (4) the Rhodes Gyre, the area of formation of the so-called Levantine Intermediate Waters (LIW) and Levantine Deep Waters (LDW). Annual water mass formation rates have been computed using daily mixed layer depth estimates (density criteria Δσ = 0.01 kg/m3, 10 m reference level) considering the annual maximum volume of water above mixed layer depth with potential density within or higher the specific thresholds specified in Table 1 then divided by seconds per year. Annual mean values are provided using the Mediterranean 1/24o eddy resolving reanalysis (Escudier et al. 2020, 2021). Time spans from 1987 to the year preceding the current one [-1Y], operationally extended yearly. '''CONTEXT''' The formation of intermediate and deep water masses is one of the most important processes occurring in the Mediterranean Sea, being a component of its general overturning circulation. This circulation varies at interannual and multidecadal time scales and it is composed of an upper zonal cell (Zonal Overturning Circulation) and two main meridional cells in the western and eastern Mediterranean (Pinardi and Masetti 2000). The objective is to monitor the main water mass formation events using the eddy resolving Mediterranean Sea Reanalysis (MEDSEA_MULTIYEAR_PHY_006_004, Escudier et al. 2020, 2021) and considering Pinardi et al. (2015) and Simoncelli and Pinardi (2018) as references for the methodology. The Mediterranean Sea Reanalysis can reproduce both Eastern Mediterranean Transient and Western Mediterranean Transition phenomena and catches the principal water mass formation events reported in the literature. This will permit constant monitoring of the open ocean deep convection process in the Mediterranean Sea and a better understanding of the multiple drivers of the general overturning circulation at interannual and multidecadal time scales. Deep and intermediate water formation events reveal themselves by a deep mixed layer depth distribution in four Mediterranean areas: Gulf of Lions, Southern Adriatic Sea Pit, Cretan Sea and Rhodes Gyre. '''KEY FINDINGS''' The Western Mediterranean Deep Water (WMDW) formation events in the Gulf of Lion appear to be larger after 1999 consistently with Schroeder et al. (2006, 2008) related to the Eastern Mediterranean Transient event. This modification of WMDW after 2005 has been called Western Mediterranean Transition. WMDW formation events are consistent with Somot et al. (2016) and the event in 2009 is also reported in Houpert et al. (2016). The Eastern Mediterranean Deep Water (EMDW) formation in the Southern Adriatic Pit region displays a period of water mass formation between 1988 and 1993, in agreement with Pinardi et al. (2015), in 1996, 1999 and 2000 as documented by Manca et al. (2002). Weak deep water formation in winter 2006 is confirmed by observations in Vilibić and Šantić (2008). An intense deep water formation event is detected in 2012-2013 (Gačić et al., 2014). Last years are characterized by large events starting from 2017 (Mihanovic et al., 2021). Cretan Intermediate Water formation rates present larger peaks between 1989 and 1993 with the ones in 1992 and 1993 composing the Eastern Mediterranean Transient phenomena. The Cretan Deep Water formed in 1992 and 1993 is characterized by the highest densities of the entire period in accordance with Velaoras et al. (2014). The Levantine Deep Water formation rate in the Rhode Gyre region presents the largest values between 1992 and 1993 in agreement with Kontoyiannis et al. (1999). '''DOI (product):''' https://doi.org/10.48670/mds-00318

-

'''DEFINITION''' The Copernicus Marine IBI_OMI_seastate_extreme_var_swh_mean_and_anomaly OMI indicator is based on the computation of the annual 99th percentile of Significant Wave Height (SWH) from model data. Two different CMEMS products are used to compute the indicator: The Iberia-Biscay-Ireland Multi Year Product (IBI_MULTIYEAR_WAV_005_006) and the Analysis product (IBI_ANALYSISFORECAST_WAV_005_005). Two parameters have been considered for this OMI: * Map of the 99th mean percentile: It is obtained from the Multi-Year Product, the annual 99th percentile is computed for each year of the product. The percentiles are temporally averaged in the whole period (1980-2023). * Anomaly of the 99th percentile in 2024: The 99th percentile of the year 2024 is computed from the Analysis product. The anomaly is obtained by subtracting the mean percentile to the percentile in 2024. This indicator is aimed at monitoring the extremes of annual significant wave height and evaluate the spatio-temporal variability. The use of percentiles instead of annual maxima, makes this extremes study less affected by individual data. This approach was first successfully applied to sea level variable (Pérez Gómez et al., 2016) and then extended to other essential variables, such as sea surface temperature and significant wave height (Pérez Gómez et al 2018 and Álvarez-Fanjul et al., 2019). Further details and in-depth scientific evaluation can be found in the CMEMS Ocean State report (Álvarez- Fanjul et al., 2019). '''CONTEXT''' The sea state and its related spatio-temporal variability affect dramatically maritime activities and the physical connectivity between offshore waters and coastal ecosystems, impacting therefore on the biodiversity of marine protected areas (González-Marco et al., 2008; Savina et al., 2003; Hewitt, 2003). Over the last decades, significant attention has been devoted to extreme wave height events since their destructive effects in both the shoreline environment and human infrastructures have prompted a wide range of adaptation strategies to deal with natural hazards in coastal areas (Hansom et al., 2015). Complementarily, there is also an emerging question about the role of anthropogenic global climate change on present and future extreme wave conditions (Young and Ribal, 2019). The Iberia-Biscay-Ireland region, which covers the North-East Atlantic Ocean from Canary Islands to Ireland, is characterized by two different sea state wave climate regions: whereas the northern half, impacted by the North Atlantic subpolar front, is of one of the world’s greatest wave generating regions (Mørk et al., 2010; Folley, 2017), the southern half, located at subtropical latitudes, is by contrast influenced by persistent trade winds and thus by constant and moderate wave regimes. The North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), which refers to changes in the atmospheric sea level pressure difference between the Azores and Iceland, is a significant driver of wave climate variability in the Northern Hemisphere. The influence of North Atlantic Oscillation on waves along the Atlantic coast of Europe is particularly strong in and has a major impact on northern latitudes wintertime (Gleeson et al., 2017; Martínez-Asensio et al. 2016; Wolf et al., 2002; Bauer, 2001; Kushnir et al., 1997; Bouws et al., 1996; Bacon and Carter, 1991). Swings in the North Atlantic Oscillation index produce changes in the storms track and subsequently in the wind speed and direction over the Atlantic that alter the wave regime. When North Atlantic Oscillation index is in its positive phase, storms usually track northeast of Europe and enhanced westerly winds induce higher than average waves in the northernmost Atlantic Ocean. Conversely, in the negative North Atlantic Oscillation phase, the track of the storms is more zonal and south than usual, with trade winds (mid latitude westerlies) being slower and producing higher than average waves in southern latitudes (Marshall et al., 2001; Wolf et al., 2002; Wolf and Woolf, 2006). Additionally, a variety of previous studies have uniquevocally determined the relationship between the sea state variability in the IBI region and other atmospheric climate modes such as the East Atlantic pattern, the Arctic Oscillation, the East Atlantic Western Russian pattern and the Scandinavian pattern (Izaguirre et al., 2011, Martínez-Asensio et al., 2016). In this context, long‐term statistical analysis of reanalyzed model data is mandatory not only to disentangle other driving agents of wave climate but also to attempt inferring any potential trend in the number and/or intensity of extreme wave events in coastal areas with subsequent socio-economic and environmental consequences. '''CMEMS KEY FINDINGS''' The climatic mean of 99th percentile (1980-2023) reveals a north-south gradient of Significant Wave Height with the highest values in northern latitudes (above 8m) and lowest values (2-3 m) detected southeastward of Canary Islands, in the seas between Canary Islands and the African Continental Shelf. This north-south pattern is the result of the two climatic conditions prevailing in the region and previously described. The 99th percentile anomalies in 2024 show that during this period, virtually the entire IBI region was affected by positive anomalies in maximum SWH, which exceeded the standard deviation of the historical record in the waters west of the Iberian Peninsula, the Spanish coast of the Bay of Biscay, and the African coast south of Cape Ghir. Anomalies reaching twice the standard deviation of the time series were also observed in coastal regions of the English Channel. '''DOI (product):''' https://doi.org/10.48670/moi-00249

-

'''DEFINITION''' Volume transport across lines are obtained by integrating the volume fluxes along some selected sections and from top to bottom of the ocean. The values are computed from models’ daily output. The mean value over a reference period (1993-2014) and over the last full year are provided for the ensemble product and the individual reanalysis, as well as the standard deviation for the ensemble product over the reference period (1993-2014). The values are given in Sverdrup (Sv). '''CONTEXT''' The ocean transports heat and mass by vertical overturning and horizontal circulation, and is one of the fundamental dynamic components of the Earth’s energy budget (IPCC, 2013). There are spatial asymmetries in the energy budget resulting from the Earth’s orientation to the sun and the meridional variation in absorbed radiation which support a transfer of energy from the tropics towards the poles. However, there are spatial variations in the loss of heat by the ocean through sensible and latent heat fluxes, as well as differences in ocean basin geometry and current systems. These complexities support a pattern of oceanic heat transport that is not strictly from lower to high latitudes. Moreover, it is not stationary and we are only beginning to unravel its variability. '''CMEMS KEY FINDINGS''' The mean transports estimated by the ensemble global reanalysis are comparable to estimates based on observations; the uncertainties on these integrated quantities are still large in all the available products. At Drake Passage, the multi-product approach (product no. 2.4.1) is larger than the value (130 Sv) of Lumpkin and Speer (2007), but smaller than the new observational based results of Colin de Verdière and Ollitrault, (2016) (175 Sv) and Donohue (2017) (173.3 Sv). Note: The key findings will be updated annually in November, in line with OMI evolutions. '''DOI (product):''' https://doi.org/10.48670/moi-00247

-

'''This product has been archived''' '''DEFINITION''' The temporal evolution of thermosteric sea level in an ocean layer is obtained from an integration of temperature driven ocean density variations, which are subtracted from a reference climatology to obtain the fluctuations from an average field. The regional thermosteric sea level values are then averaged from 60°S-60°N aiming to monitor interannual to long term global sea level variations caused by temperature driven ocean volume changes through thermal expansion as expressed in meters (m). '''CONTEXT''' Most of the interannual variability and trends in regional sea level is caused by changes in steric sea level. At mid and low latitudes, the steric sea level signal is essentially due to temperature changes, i.e. the thermosteric effect (Stammer et al., 2013, Meyssignac et al., 2016). Salinity changes play only a local role. Regional trends of thermosteric sea level can be significantly larger compared to their globally averaged versions (Storto et al., 2018). Except for shallow shelf sea and high latitudes (> 60° latitude), regional thermosteric sea level variations are mostly related to ocean circulation changes, in particular in the tropics where the sea level variations and trends are the most intense over the last two decades. '''CMEMS KEY FINDINGS''' Significant (i.e. when the signal exceeds the noise) regional trends for the period 2005-2019 from the Copernicus Marine Service multi-ensemble approach show a thermosteric sea level rise at rates ranging from the global mean average up to more than 8 mm/year. There are specific regions where a negative trend is observed above noise at rates up to about -8 mm/year such as in the subpolar North Atlantic, or the western tropical Pacific. These areas are characterized by strong year-to-year variability (Dubois et al., 2018; Capotondi et al., 2020). Note: The key findings will be updated annually in November, in line with OMI evolutions. '''DOI (product):''' https://doi.org/10.48670/moi-00241

-

'''DEFINITION''' Meridional Heat Transport is computed by integrating the heat fluxes along the zonal direction and from top to bottom of the ocean. They are given over 3 basins (Global Ocean, Atlantic Ocean and Indian+Pacific Ocean) and for all the grid points in the meridional grid of each basin. The mean value over a reference period (1993-2014) and over the last full year are provided for the ensemble product and the individual reanalysis, as well as the standard deviation for the ensemble product over the reference period (1993-2014). The values are given in PetaWatt (PW). '''CONTEXT''' The ocean transports heat and mass by vertical overturning and horizontal circulation, and is one of the fundamental dynamic components of the Earth’s energy budget (IPCC, 2013). There are spatial asymmetries in the energy budget resulting from the Earth’s orientation to the sun and the meridional variation in absorbed radiation which support a transfer of energy from the tropics towards the poles. However, there are spatial variations in the loss of heat by the ocean through sensible and latent heat fluxes, as well as differences in ocean basin geometry and current systems. These complexities support a pattern of oceanic heat transport that is not strictly from lower to high latitudes. Moreover, it is not stationary and we are only beginning to unravel its variability. '''CMEMS KEY FINDINGS''' After an anusual 2016 year (Bricaud 2016), with a higher global meridional heat transport in the tropical band explained by, the increase of northward heat transport at 5-10 ° N in the Pacific Ocean during the El Niño event, 2017 northward heat transport is lower than the 1993-2014 reference value in the tropical band, for both Atlantic and Indian + Pacific Oceans. At the higher latitudes, 2017 northward heat transport is closed to 1993-2014 values. Note: The key findings will be updated annually in November, in line with OMI evolutions. '''DOI (product):''' https://doi.org/10.48670/moi-00246

-

'''This product has been archived''' '''DEFINITION''' Estimates of Ocean Heat Content (OHC) are obtained from integrated differences of the measured temperature and a climatology along a vertical profile in the ocean (von Schuckmann et al., 2018). The regional OHC values are then averaged from 60°S-60°N aiming i) to obtain the mean OHC as expressed in Joules per meter square (J/m2) to monitor the large-scale variability and change. ii) to monitor the amount of energy in the form of heat stored in the ocean (i.e. the change of OHC in time), expressed in Watt per square meter (W/m2). Ocean heat content is one of the six Global Climate Indicators recommended by the World Meterological Organisation for Sustainable Development Goal 13 implementation (WMO, 2017). '''CONTEXT''' Knowing how much and where heat energy is stored and released in the ocean is essential for understanding the contemporary Earth system state, variability and change, as the ocean shapes our perspectives for the future (von Schuckmann et al., 2020). Variations in OHC can induce changes in ocean stratification, currents, sea ice and ice shelfs (IPCC, 2019; 2021); they set time scales and dominate Earth system adjustments to climate variability and change (Hansen et al., 2011); they are a key player in ocean-atmosphere interactions and sea level change (WCRP, 2018) and they can impact marine ecosystems and human livelihoods (IPCC, 2019). '''CMEMS KEY FINDINGS''' Since the year 2005, the near-surface (0-300m) near-global (60°S-60°N) ocean warms at a rate of 0.4 ± 0.1 W/m2. Note: The key findings will be updated annually in November, in line with OMI evolutions. '''DOI (product):''' https://doi.org/10.48670/moi-00233

Catalogue PIGMA

Catalogue PIGMA